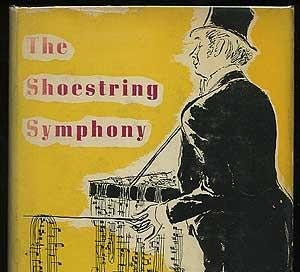

“Get to the point, Edna.” Edna was Judi’s kind and devoted grandmother. Her sister was the source of that mildly rude comment. Edna’s stories would go on for over fifteen minutes, with parenthetical remarks gaining prominence. Judi and I were too young or polite to tell Edna to get to the point, so when we visited her in her Mt. Vernon apartment Judi would sit and listen to her grandmother telling the same stories she’d already heard. Meanwhile I would quietly walk out of the small dining area to her living room where her bookshelves were. That’s where I found The Shoestring Symphony by Dutch movie music composer David Broekman, a very fictionalized account of his Depression-era life in Hollywood published in 1948. Edna let me keep the book. We read it and loved it. Years later, we wrote a musical theatre piece based on it. Here’s the synopsis:

Composer David Broekman is heavily in debt. His neighbor, the silent-film producer S.T. Hawkins, refers him to entrepreneur Pierre Tuttle, an expert in being able to manipulate a situation to make a profit and keep all of it in his own pocket(s).Hawkins loans David the use of a makeshift office with only one chair and little else in order to set up a meeting with Tuttle. Unexpectedly, David interests Tuttle with a “Negro Symphony” he has recently begun, because he tells him that the work will be presented at the Hollywood Bowl—a complete lie. Tuttle, who admits to having no interest in music whatsoever, relishes the idea of making a fortune selling out the 27,000-seat Hollywood Bowl. This appears to be a poor investment, since it seems unlikely that this work by an unknown composer would even make a profit.

David decides to have a gospel choir sing in the symphony’s finale, and realizes that he needs an African-American librettist. Searching through the Yellow Pages, after several pages of entries for “Moroccan librettists” he finds under “Negro Librettists” the name of Harrison Ballew, “Dr. Showman Emeritus.” Harrison is a proud man who is embittered by the racial climate of show business. He has appeared in many motion pictures, invariably as a slave. Harrison considers that this work will give “his people” the symphony that they deserve. Harrison is prone to use the “race card” in order to gain acceptance among progressive-thinking whites.

Harrison learns that David has formed a partnership with Tuttle, for which he is getting paid two dollars a day. So Harrison must become a third partner in the endeavor, which has the unlikely name of TWATTGOH, Inc., or “The Walk Through the Garden of Heaven.” Harrison hates business people who interfere with the creative process. He takes an immediate dislike to Tuttle, and the pair continue to just barely coexist.

This unlikely trio manage to succeed in persuading the Hollywood Bowl committee to present the work. Tuttle with his assistant, the racist alcoholic ad man Eddie Jenks, manage to fill the entire amphitheater. In the meantime, Tuttle manages to swindle David and even Harrison, the ever-vigilant and experienced “showman emeritus,” out of most of the money.

A subplot of “The Shoestring Symphony” is the relationship between the washed-up producer S.T. Hawkins and his much younger wife, Cappy. Now an out-of-work actress in her late thirties, Cappy has been promised by her husband that he’ll make her a star. In order to get himself back as a Hollywood player, the “Hawk” gets a friendly reporter to write a newspaper story that carries the headline, “S.T. Hawkins, Pioneer Producer, Offers Jean Harlow $150,000 to Star in New Picture.” Everything about the story is fraudulent, but Cappy is incensed. Nothing comes of the Hawk’s machinations.

The Shoestring Symphony had two lives after it was published. In its first life, Judi showed the book to her brother Richard Weinstock. She thought it would be a great vehicle as the basis of a musical, and he could involve me to write the orchestral sections. Richard was smitten with the book, and he brought the idea to Gail Merrifield Papp, the wife and partner of Joseph Papp at the Public Theatre, who liked Richard and his music. Gail paired Richard with a librettist named Anthony Giles and supplied some funding. I never thought about it before, but these events parallel the storyline of the Shoestring Symphony: the wily manager Pierre Tuttle likewise introduces Broekman to a librettist who adds words to a section of the symphony that Broekman is commissioned for $2 a day. After auditioning the piece for Joe Papp and his wife, the project never went any further.

After Richard died we couldn’t find any of his music. All that existed was a recording of the song “I Could Have been Jean Harlow” in a recording with singer Sharon McNight, who Richard was the musical director for and piano player. The text was in the libretto, and I transcribed the music from the recording. Ten years later Judi and I decided to tackle the Shoestring Symphony. We retained the “Jean Harlow” song and most of Anthony Giles’ libretto but the rest was our own work. I sent our results to The Golden Fleece, Ltd., an independent musical theatre group led by American opera singer, playwright and composer Lou Rodgers, and they expressed interest in staging the beginning section of the piece. It was a wonderful experience to see the music come to life in a handful of performances at a rented theatre in NYC.

“Plainspoken Man,” a portrait of the composer by his wife, was one of Judi’s best lyrics in the Shoestring Symphony:

He never remembers to brush his hair. As for his clothes—he doesn’t care. He isn’t slick, he isn’t proud; he’s floating on his private cloud. He’s just a plainspoken man living his dreams the best he can. He doesn’t have expensive taste. His shoelaces are rarely laced. He doesn’t schmooze, preen or flatter. It wouldn’t occur to him it mattered. He’s just a plainspoken man living his dreams the best he can.

His last boss said his music was effete. “Does it have a melody? Where’s the beat?” His music was too highbrow for the brows out here. “Go back to Europe or get back in gear!” But he doesn’t conform to other’s norms. He doesn’t compromise when he performs. He’s an artist, he’s for real. Even if we have to beg, borrow or steal my guy will stay a plainspoken man, trying to live his dreams the best he can! Call him a fool, call him a clown. For rich or poor, for up or down—I’ll be around to see things through until this plainspoken man gets his due!

Here’s Kris Adams singing “Plainspoken Man” with Syberen Munster, guitar, John Loehrke, bass, Eva Gerard, viola, Charley Gerard, alto saxophone and drummer Danny Wolf.

/songs-by-judith-weinstock-and&si=bb74b5556b79446195767a359cc80910&utm_source=clipboard&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=social_sharing

Wonderful!